Case 14 - coma and dilated pupil

What is the lesion?

Tempo is everything, and this patient was well yesterday, then in a coma today with multiple signs present. We don’t know what happened in the interim but it happened quickly, whether suddenly or over minutes or hours until she was found by her daughter.

VascularA vascular lesion is by far the most likely cause. She also has several relevant risk factors, including age, hypertension, atrial fibrillation (for ischaemia) and anticoagulation therapy (for haemorrhage).

A massive ischaemic stroke is possible – but if so, then uncal herniation would be unusual this quickly. The type of cerebral oedema associated with this – termed malignant or space-occupying infarction – often peaks within 24-48 hours after onset, and is particularly seen in younger patients – whose brains swell up more avidly, and who have less age-related volume loss, so the effect is more severe, with mass effect as the brain expands. At this age and this early into the event, it’s less likely.

It could of course be a deeper ischaemic stroke involving some of the structures mentioned before - including basilar artery-supplied territories.

A massive intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) into the right hemispheric parenchyma is very possible. This would quickly expand and cause mass effect and herniation, explaining the III palsy. It would explain hemiparesis too. She is also on an anticoagulant which increases the risk of ICH, as does her hypertension.

Another important site for haemorrhage leading to coma is the posterior fossa. Blood in that area is poorly accommodated, with sharp pressure rises and mass effect on brainstem and cerebellar structures, rapidly- falling consciousness, and often hydrocephalus. Blood may also spill into the ventricles. This is also a consideration although we might see other signs of this (e.g. vertical nystagmus) and it less easily explains the eye deviation and III palsy.

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) due to aneurysmal rupture into the cisterns around the base of the brain could explain coma, and as above, a PCom aneurysm might compress III. Paralysis can be seen in higher-grade (i.e. more extensive) haemorrhages.

Another clue to a vascular catastrophe is the hypertension – often seen as a reaction to strokes, and an important target for rapid modification in haemorrhage.

Other considerationsBeyond vascular aetiologies there are not many candidates that would explain this. Coma is often due to metabolic disorders such as hypoglycaemia or hypercapnia but the focal neurological signs strongly imply structural pathology. Very few inflammatory lesions would develop as fulminantly as this, likewise tumours – even though they can sometimes lead to rapid neurological deterioration, for example through haemorrhage or ventricular obstruction and hydrocephalus.

A neurological infection is an important consideration and people can quickly neurologically deteriorate – but there are no additional clues for this being meningitis such as fever or meningism, and it would be extremely fast for viral encephalitis, which typically takes several days to peak and cause coma.

Seizures can produce coma and sometimes do not produce visible movements (i.e. non-convulsive status epilepticus). This may feature signs such as forced eye deviation and sometimes pupil abnormalities can be seen, so this is a possibility – but it feels much more likely that there will be a structural mass underlying this.

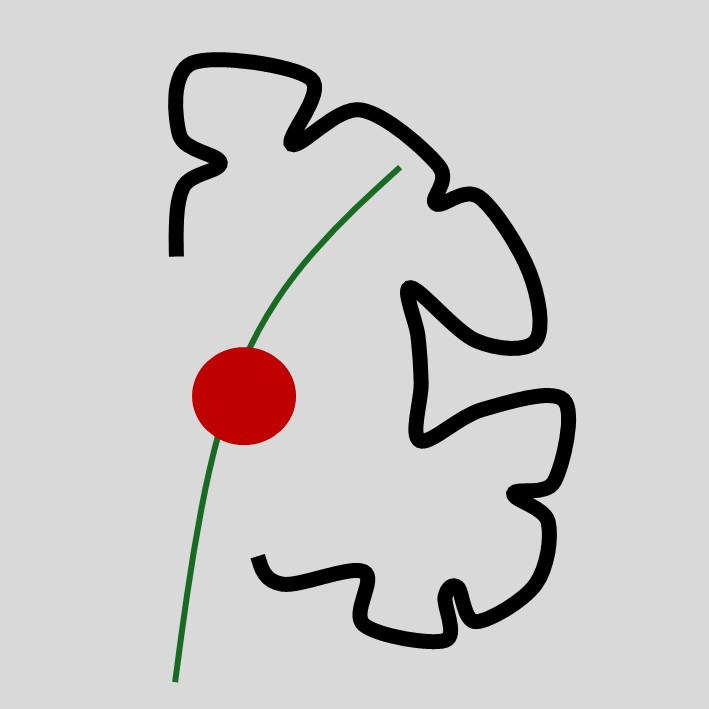

SummaryThe most likely cause is vascular and the chief worry is a large right hemispheric haemorrhage causing mass effect and herniation.

Clinical formulation