Case 13 - numb hands and stiff legs

What is the lesion?

Many causes of myelopathy exist. What will help us work out the likely cause is the tempo and the clinical features - because those reflect the structures involved, and various lesions tend to affect certain parts of the cord.

There are various terms used here which can overlap, so some definitions are given in the box below.

Myelitis – inflammation of the spinal cord (inflammatory myelopathy)

Myelopathy -spinal cord disease, of any kind - though 'myelopathy' is often used to mean ‘compressive cervical myelopathy’, usually due to discs or other degenerative pathologies.

Myeloneuropathy -combination of cord and peripheral nerve disease (e.g. B12 deficiency)

Radiculitis – inflammation at a root (e.g. from infection such as Lyme disease)

Radiculopathy - compression of a root, by any cause (though often used to imply a disc prolapse)

Spondylolisthesis - anterior slippage of one vertebral body on top of another

Spondylosis - age-related degeneration of the vertebral column (including disc prolapse, osteophytes, facet joint hypertrophy)

The tempo is progressive over weeks-months. We are not dealing with a stroke, and the tempo is slow for inflammation of the cord itself (myelitis) - although some inflammatory processes affect the meninges or cause masses and can progress subacutely and contact the cord.

We broadly divide into compressive and non-compressive forms. This is helpful when assessing patients with myelopathy and thinking through causes. It's also often the primary 'pivot point' as compressive lesions may need urgent surgical management, so is the major question we assess via imaging - if no compressive lesion we then may have to explore a range of other causes. Compressive lesions are evident on imaging, while some but not all non-compressive ones are visible.

1. Compressive myelopathyA major consideration here is compression. This can present over the time frame here. There are various causes of this:

Degeneration is very common and asymptomatic degenerative changes are the norm for people as they age, most of whom will never experience any neurological manifestations of these. We get older, discs bulge and lose height, bones grow spurs (osteophytes) which narrow the canal or exit spaces, and ligaments thicken and harden. This combination narrows the space around the cord without damaging its parenchyma, but also creates a vulnerable environment - further intrusions can compromise the cord easily, causing symptoms. If a disc then prolapses, this can compress the cord, leading to myelopathy. Typically the compression is of the anterior, central and lateral cord. The dorsal columns are not involved as they are furthest away.

Tumours can grow in the cord (intramedullary) our outside of it (extramedullary), and depending where they grow, the symptoms can vary. Tumours within the cord may directly invade and disrupt the parenchyma or the CSF flow. Those outside of it whether intra- or extradural, can compress whatever aspect of it they contact. There may be additional features such as back pain, particularly at night. In cases of metastatic tumour, which are usually extradural, there may be additional cancer-associated symptoms such as weight loss.

A syrinx is a central cyst within the spinal cord, leading to syringomyelia - a compressive condition with distortion of the surrounding tracts. The typical presentation is combined spinothalamic sensory loss in the upper limbs (leading to loss of pain and temperature sensation and a tendency to burns) with a central cord syndrome pattern including weak and wasted hands (often with clawing, resembling ulnar nerve lesions) due to anterior horn cell involvement.

Vascular compressive lesions of the cord include AMV, dAVF and cavernomas. These can present similarly to tumours though also can acutely present, or worsen, due to haemorrhage, and presentations may fluctuate. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is also possible, with blood travelling up into the intracranial space causing headache, as well as severe back pain compared to being stabbed with a dagger (Coup de poignard of Michon). dAVFs are often lower down so can affect the conus in addition to the lower thoracic zone; symptoms may be progressive but also dynamic - worsening on standing and exertion due to increasing venous congestion and steal phenomena.

Infection-related compressive lesions include abscess in the epidural space which can present with weakness, sensory deficits, pain (including radicular) and fever. Similar is true of disciitis which can cause neurological symptoms if there is compression of the cord.

A compressive condition is a concern here - particularly degeneration-related, with a disc protrusion compressing the cord from the front, which is common - or alternatively a tumour. A vascular lesion is possible too. There are no features to suggest infection and the tempo seems a little slow for such conditions - although some can be very indolent and chronic, including tuberculosis-related spinal complications.

2. Non-compressive myelopathyThis refers to more 'intrinsic' problems in the cord rather than a physical lesion squashing it.

Spinal cord stroke and haemorrhage generally presents hyperacutely so this doesn't fit this case. Myelitis (inflammatory myelopathy) also tends to come on over several days rather than 3 months so also is not likely here.

Metabolic disorders are important causes of myelopathy, and many can affect the cord. The distribution of cord damage plus the presence of other features can be a clue. The commonest is B12 deficiency, which tends to produce a combination of dorsal column disease as well as neuropathy, with motor signs less common - the exact opposite of this patient's situation. Other deficiencies can produce spasticity and UMN damage, for example copper deficiency and vitamin E deficiency, so a metabolic myopathy is a possible consideration. Again though there are often additional features such as neuropathy - because it isn't just the spine that depends on these nutrients.

Neurodegenerative disorders present over months and years. While various degenerative myelopathies exist, including genetic forms, they don’t seem likely here from the short duration and quick progression over weeks. Motor neuron disease (MND) is important to consider - the commonest form, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), features quickly progressive UMN signs co-occurring with LMN signs and bulbar features, arising over months. This patient has UMN signs alone which are near-symmetrical, which is atypical for ALS, and they affected all four limbs from the start, which is also atypical: ALS tends to produce focal problems in one segment (e.g. a weak hand) then another (e.g. altered speech or a weak leg) and is often asymmetrical. A UMN-only form of MND, primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), exists, and can look similar to the features in this case - but is much slower, with unusually long survival for MND (decades).

Infectious myelopathies include disorders such as HIV and syphilis which directly lead to degeneration in the cord, tropical spastic paraparesis (due to HTLV-1) which slowly evolves over decades, as well as compressive infectious problems as above. Unlike the usual compressive infectious causes, these degenerative patterns can progress very slowly and without systemic manifestations such as fever or pain. It’s possible this patient has such a disorder, but they're rarer than commoner conditions such as degeneration-related compression, so it seems less likely.

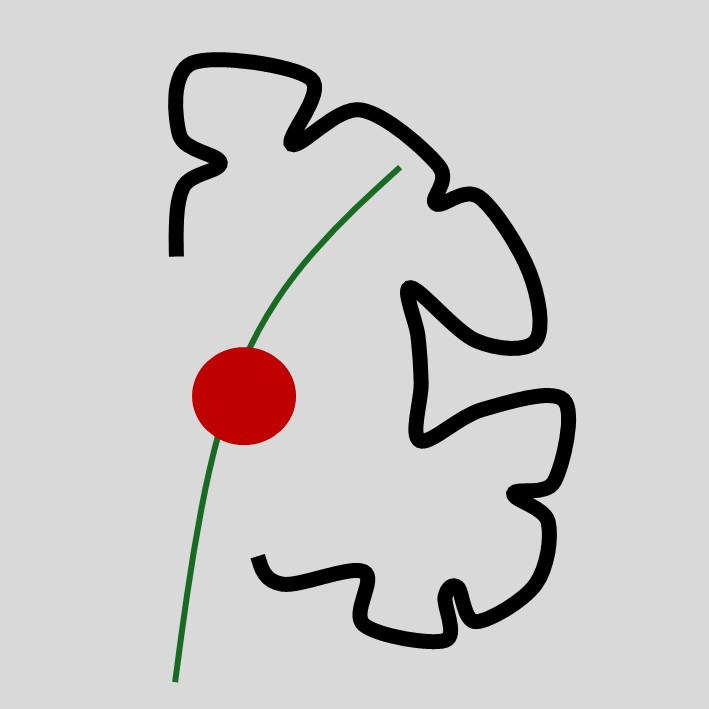

SummaryPutting this together, the concern is of a progressive myelopathy with an anterior-central pattern of features, and compressive causes are a big concern, particularly degeneration-related. Imaging is key, and if that doesn't explain things we may have to consider some of the more unusual non-compressive causes.

Clinical formulation