Case 19 - Memory problems

Where is the lesion?

Tackling this requires knowledge both of the tempo - which tells us the majority of what we need to know about underlying lesions - but also the repertoire of disorders that can produce anterograde amnesia. We are looking for something that would come on over several weeks and characteristically affects this area of the brain.

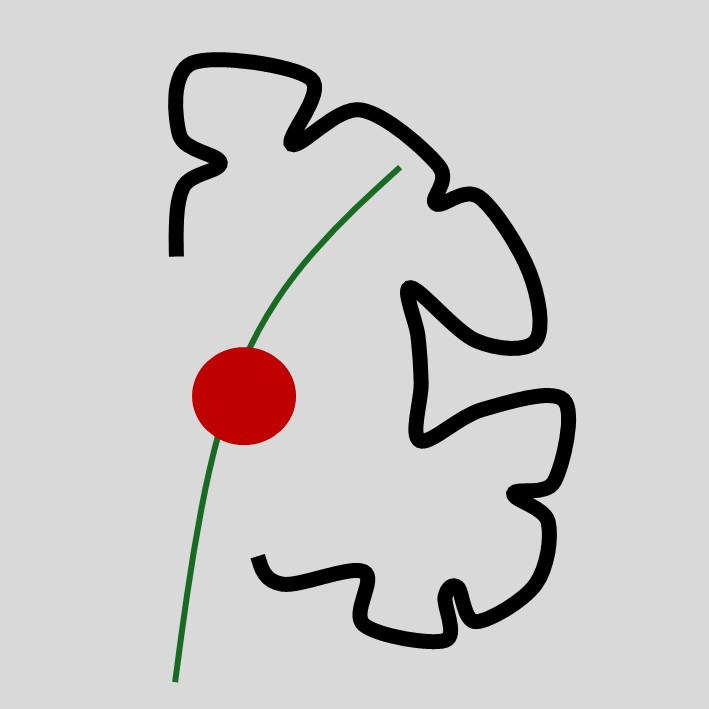

A wide spectrum of disorders, affecting various components of the Papez circuit, can affect the ability to lay down and retrieve new memories.

Transient amnesiaAcute, transient amnesia (under 24 hours) can happen for a few causes. An important, benign one is transient global amnesia (TGA) - which causes an amnesia very much like our patient's case, with no other cognitive problems associated, but only lasting a few hours. It is benign. The hippocampi can show changes if an MRI is done during an attack. It's not a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or a seizure, and we don't really know what it actually is. Other problems leading to transient amnesia include substance misuse, but there are other features beyond amnesia (for example disinhibition and ataxia with alcohol intoxication).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, slowly progressive amnesia is usually due to Alzheimer's, the commonest dementia. There are other dementias which also cause it but they're less common. It doesn't present anywhere near as rapidly as our patient's case.

Acute and subacute amnesiaVarious vascular, metabolic, infectious and inflammatory disorders dominate the landscape of amnesia occurring in this tempo (seconds-hours-days-weeks). Neurodegenerative causes of amnesia are typically much slower, bar one uncommon but very important disease.

StrokeInterestingly a hippocampal infarct rarely causes a dense anterograde amnesia - bilateral damage is probably necessary. However, two other sites can cause amnesia from stroke. Firstly, the fornix (a potential complication of anterior communicating artery aneurysm clipping), and secondly the thalamus (not just the anterior but also dorsomedial part, particularly in the left thalamus). Both can lead to temporary or even permanent amnesia - a 'strategic' infarct that causes dementia. Thalamic infarcts often produce somnolence, broader cognitive changes such as altered attention, and a mild form of dysphasia called thalamic aphasia - with mild word-finding difficulties being the most prominent element.

There are also reports of mamillary body infarcts causing amnesia but this is unusual. The cingulate can also be affected but cingulate damage often leads to a more profound state of apathy and abulia - inability to initiate goal-orientated tasks and make decisions.

This case doesn't sound quite as sudden-onset and fixed as a stroke should be - her relatives say it is evolving daily.

Hypoxic injuryThe hippocampi are highly sensitive to hypoxia, arguably more so than other brain regions, and hypoxia can quickly damage them. In people who survive cardiac arrest, the hippocampi can be badly damaged, even relative to other brain regions - causing significant deficits in the ability to make new memories. However there is no suggestion of any hypoxic insult here.

Toxic exposuresDrug and alcohol toxicity are important considerations in acute cognitive disorders, and these are not always reported directly or admitted to on questioning - including by relatives. Surrogate markers are helpful, such as increased mean cell volume (MCV) and gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) or signs of cirrhosis, but they are not always present. Drug screens can help. Isolated amnesia is unusual though - there are usually other aspects of the cognitive syndrome (i.e. a broader encephalopathy/delirium or psychiatric disturbance) and there may be physical features, neurological and systemic. This sounds more like a progressive problem, and is isolated amnesia alone, though drug abuse is not impossible.

Metabolic disordersWernicke's encephalopathy (WE) due to thiamine deficiency is a very important consideration in anyone with new-onset memory problems. The full triad includes ophthalmoplegia (usually VI palsy) and ataxia, but many cases only have 1-2 features. People with nutritional problems are at risk of WE, and this can include recent metabolic stressors such as pregnancy with hyperemesis. In general our threshold should be very low to think of WE in new-onset amnesia or ataxic presentations and give vitamin cover while investigating for alternative causes. Permanent brain damage can otherwise arise.

As far as we know there is no relevant history for alcoholism or nutritional insufficiency. The syndrome is also a very isolated anterograde amnesia without any other features, and has been going on for 3 weeks. WE seems less likely.

Memory impairment can be seen as part of other metabolic disorders such as liver or renal failure, hypercalcaemia or thyroid dysfunction. However, usually the pattern is of a broader encephalopathy with fluctuating attention and disorientation, progressing to frank coma if not treated. Profound, isolated amnesia in an otherwise awake, alert and cooperative patient is not likely, and this patient does not sound likely to have to have a metabolic encephalopathy (and has already had a reasonable screening panel return as normal).

InfectionThis is a concern for certain. An acute or subacute progressive memory disorder raises alarm for viral encephalitis. The commonest cause is herpes simplex virus (HSV) and it characteristically affects the mesial temporal lobes and broader limbic system. The presentation is with rapidly evolving symptoms over days, usually a combination of confusion, amnesia, dysphasia, seizures and then coma. Without treatment, the majority die, and with it, between 1/4 to 1/3 still do.

Multiple other viruses also can cause a similar limbic presentation though others tend to affect other brain regions (e.g. basal ganglia with Japanese Encephalitis, brainstem with Enterovirus).

Infectious encephalitis is definitely a concern for this patient, and can happen even without a fever. Amnesia is an important symptom and may be the earliest one. However, her problem has evolved more slowly than is typical, as above. She seems far too well to have had viral encephalitis for 3 weeks - we would expect a far quicker evolution or even death.

InflammationInflammatory causes of encephalitis exist. There are two main groups: it happens either as a primary autoimmune condition, or as a paraneoplastic response to a cancer elsehwere in the body.

Autoimmune encephalitis is mostly driven by antibodies to surface receptors, for example neurotransmitter receptors (NMDA, AMPA, GABA). Diverse effects can arise but many cause a limbic encephalitis - featuring subacute onset of amnesia and often behavioural disturbance and seizures.

Paraneoplastic encephalitis is often associated with an antibody to an intraneuronal target (e.g. Hu, Ma2, Ri) which probably isn't directly causative but is a marker of an immune process damaging the brain. The antibody helps trace the cancer as certain tumours are associated with specific antibodies and syndromes. Presentations vary, but limbic encephalitis is an important pattern. Importantly, the neurological syndrome may precede detection of the cancer - and in some cases the cancer is not detectable until months later. The mainstay of treatment is treating the cancer - immunotherapy helps some forms but in others has little evidence of any effect, unfortunately.

Could this patient have autoimmune or paraneoplastic encephalitis? The tempo is consistent – acute-subacute – slower than in infectious forms. The cognitive pattern is correct (amnesia). She doesn’t have seizures, or any focal features. Sleep disturbance is something that can be seen in various forms. The fact she has had a prior cancer raises concern for recurrence manifesting as a paraneoplastic syndrome - and she's also a smoker, so could have a new cancer driving this.

Prion diseaseCreutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rapidly-progressive neurodegenerative disease due to build-up of misfolded proteins in the brain. Rapidly-progressive dementia (onset and progression over weeks) is the hallmakr, and some people would present with amnesia such as this patient, though typically other cognitive problems co-occur (including frontal or visuospatial problems). Very soon, other features emerge, including visual disturbance, ataxia and myoclonus, which are not present here - though it's early. CJD is definitely a concern in this case in addition to encephalitis.

SummarySubacute amnesia and sleep disturbance is suspicous for non-infectious encephalitis, and the smoking and prior cancer make paraneoplastic encephalitis a real concern, though it could be autoimmune. Prion disease is also in the differential. This doesn't feel consistent with infection (it's too slow), though it should be considered too.

Clinical formulation