Case 18 - Double vision and jumping eyes

Where is the lesion?

Let's review the symptoms first.

The patient has acute-onset binocular diplopia, which indicates a problem with eye alignment (unlike monocular diplopia, which reflects eye pathology). There is something wrong with the systems that normally move the eyes in a conjugate manner. This could implicate brainstem nuclei and tracts, the cranial nerves, neuromuscular junction (NMJ, as in myasthaenia gravis), and the extraocular muscles.

The additional vertigo is concerning for pathology in the posterior fossa - vertigo with any central signs is always concerning for this, and not what is seen in vestibular diseases.

Secondly, there are numerous abnormal signs:

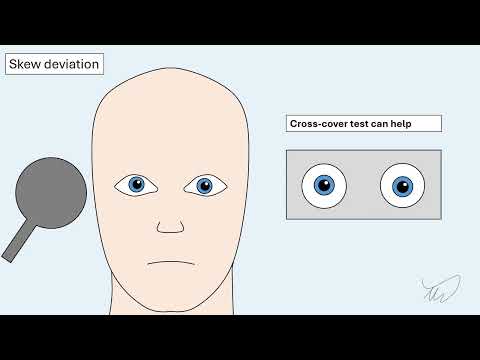

1. Skew deviationSkew deviation means vertical misalignment of the eyes not due to a single nerve palsy (e.g. IV) or individual muscle being paralysed. His right eye is sitting higher than the left, and when the left is covered, the right drifts down to take up fixation.

This implies damage in the brainstem or cerebellum though it doesn't precisely localise. It's a problem with the tonic balance between the two eyes vertical positioning, so they drift out of plane with each other.

It does however take us away from more peripheral lesion sites such as cranial nerves or the NMJ. Hypertropia is seen with IV palsy due to paralysis of superior oblique, and sometimes in paralysis of the inerior division of III, with the eyeball depressor muscles weakened and preservation of the elevators, but the signs don't fit either of these.

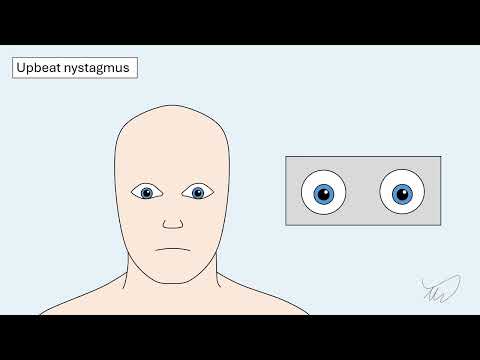

2. Upbeat nystagmusUpbeat nystagmus is a marker of central nervous system pathology - it is not seen in vestibular (peripheral) causes of vertigo. Again, it doesn't localise exactly but brainstem and cerebellar lesions can both cause it.

3. Torsional nystagmus

3. Torsional nystagmus

Torsional nystagmus is less specific – it can be seen in central lesions, though is common in vestibular pathology, but with horizontal nystagmus co-existing. Isolated torsional nystagmus is more concerning for a central lesion, and in combination with upbeat nystagmus, there is definitely a central cause.

4. Right internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO)

4. Right internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO)

This is the most useful sign here from the perspective of localisation.

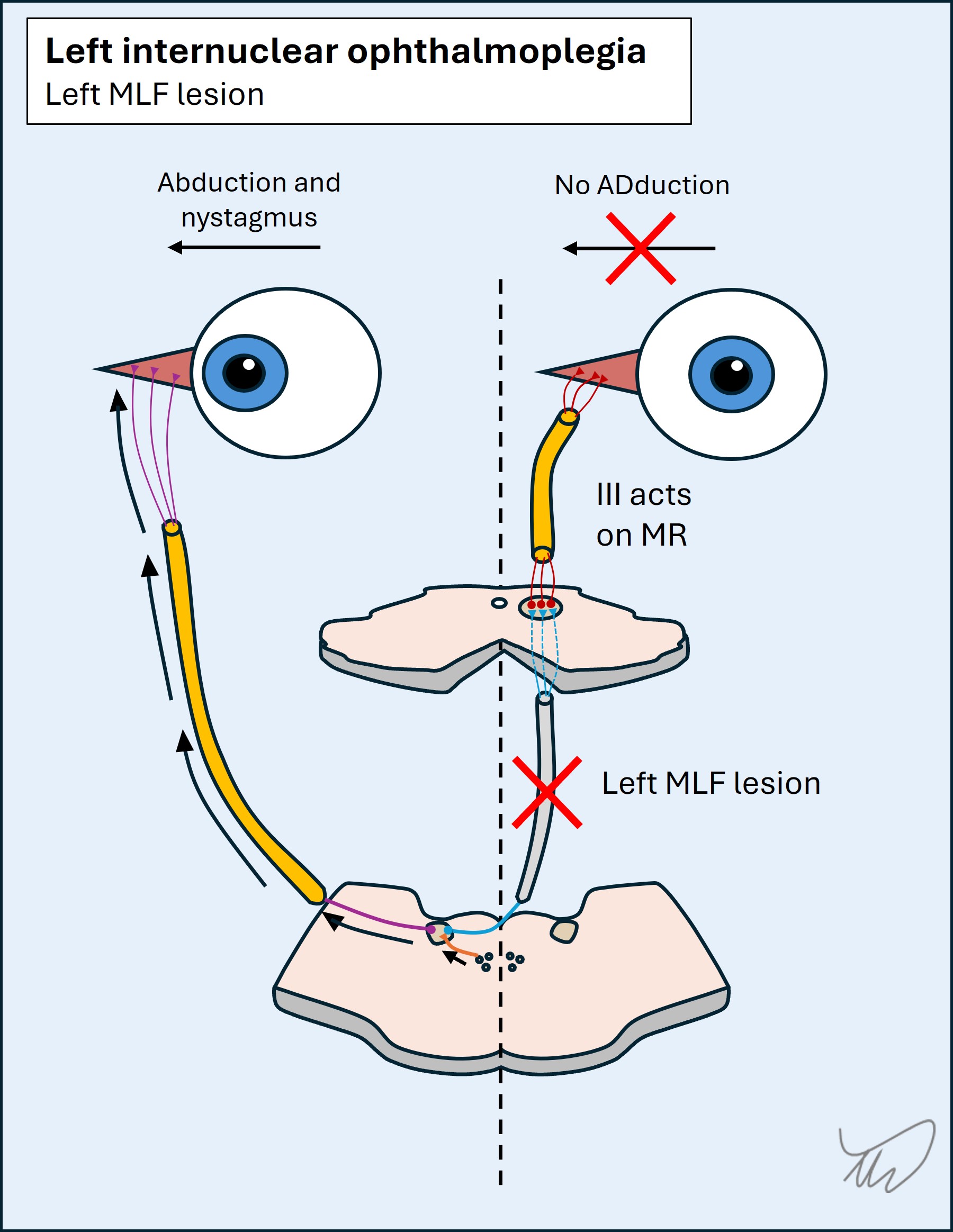

The patient cannot adduct the right eye past the midline when attempting to look left. While this is seen in a III palsy too, there would be other features of this - and there are none. Furthermore, it isn't true paralysis - he can still adduct the eye during convergence. The problem is with conjugate horizontal left gaze.

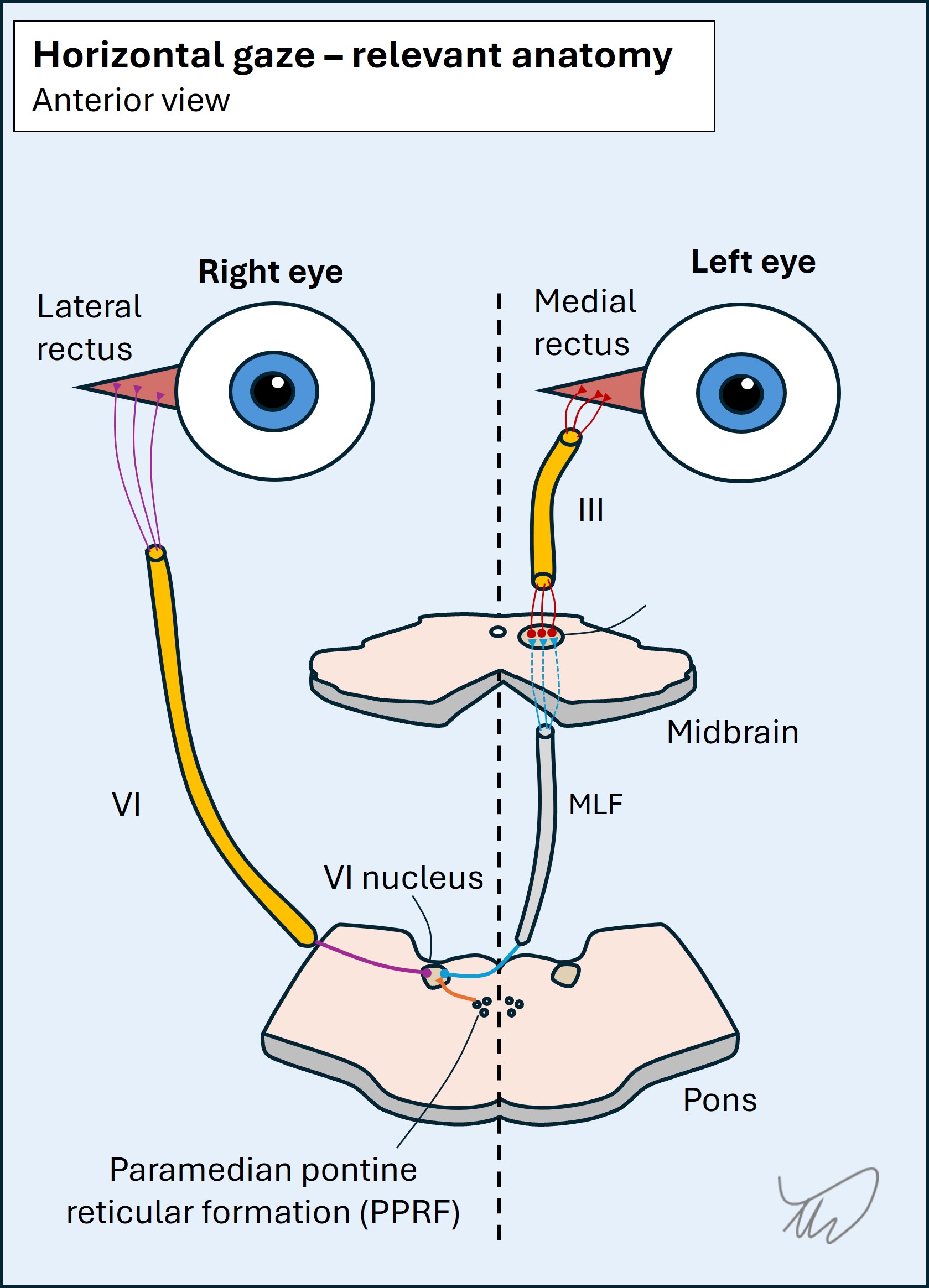

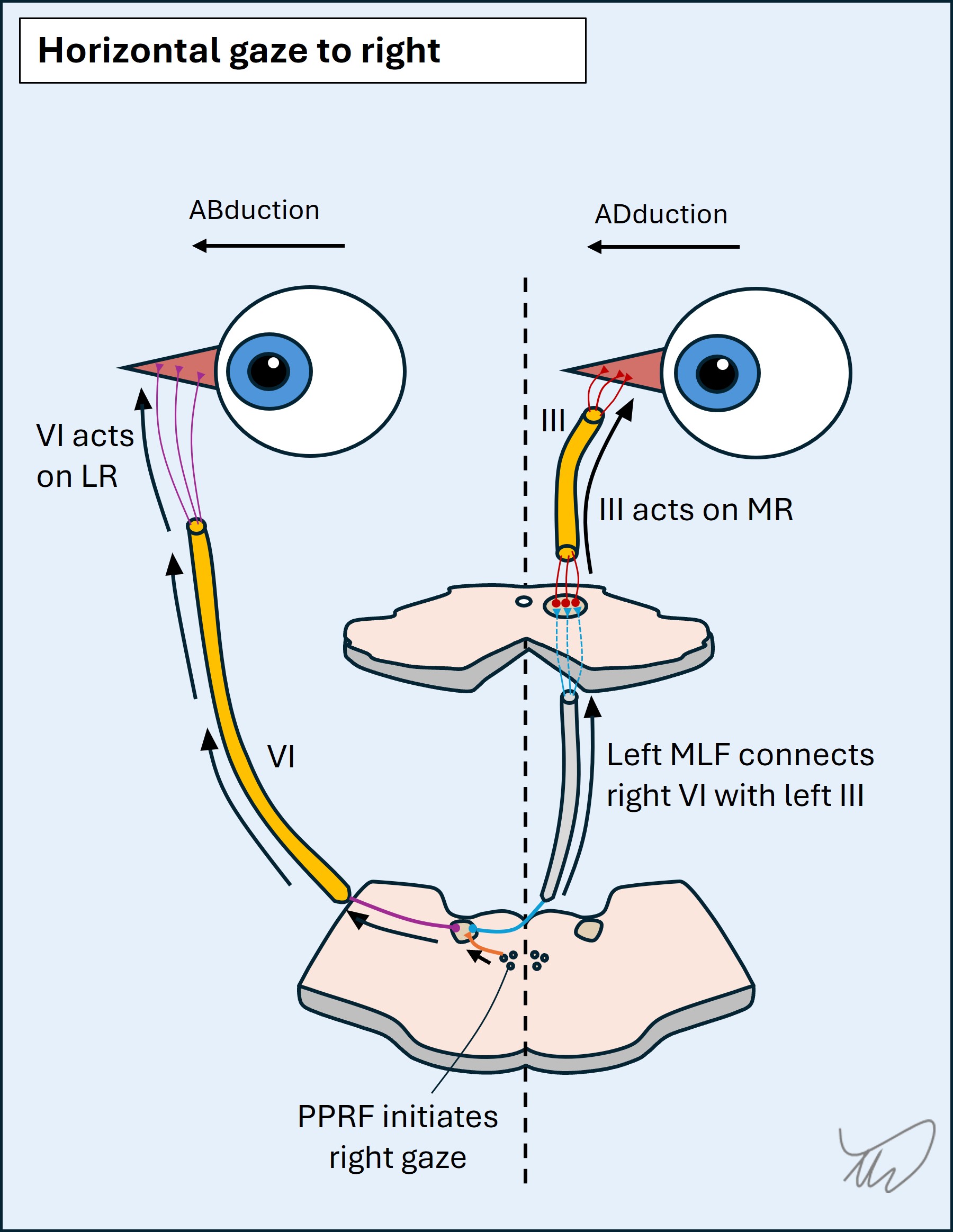

Conjugate horizontal left gaze requires both eyes to move to the left in a coordinated manner. There are a few steps to this but the end result is activity in left VI and right III to their target muscles - the lateral and medial recti on opposite sides. They need a way of communicating this, and this is via the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) - an interneuron connecting two nuclei. The full process is as follows:

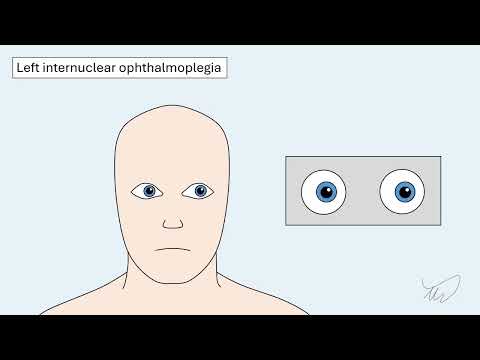

Right internuclear ophthalmoplegia localises to the right medial longitudinal fasciculus. The issue is with the communication between the left VI and right III nuclei, hence it is internuclear. The left VI can stull fully abduct - but then because of the imbalance between sides, often develops nystagmus, drifting back towards the 'stuck' right eye which can't pass the midline - as is the case in this patient.

Note - adduction is not totally paralysed. III can still adduct the eye during convergence, which doesn't involve this pathway. The problem is internuclear, and only relevant to conjugate horizontal gaze. This is called dissociation of convergence. It's important to test convergence in people who can't adduct an eye, or either eye - bilateral INO is quite common, given how close together the MLFs are either side of the midline!

The overall effect is shown in the video below.

Convergence helps us even more in localisation. A lesion in the MLF as it ascends through the pons leaves convergence intact - but a lesion higher up in the midbrain can lead to INO with impaired convergence, as the centres involved in convergence can also be damaged at this level.

Other signs that aren't presentWe can sometimes take things further - as the MLF is near many other brainstem structures, and if they are lesioned too, a more complex picture emerges.

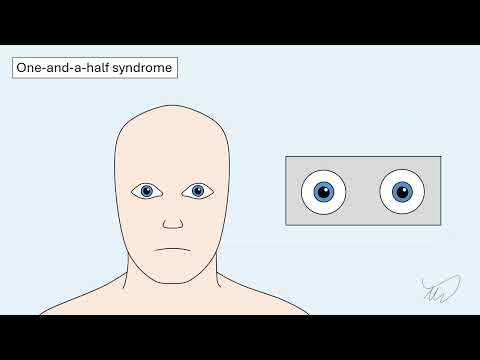

One example is when the PPRF is also affected on the same side. For a right-sided inferior dorsal pontine lesion the consequence is paralysis of right conjugate gaze (neither eye moves) and also of right eye adduction during conjugate left gaze (right INO). The only eye moving horizontally is the left eye which abducts. This combination is referred to as one-and-a-half syndrome - because there is paralysis of all of gaze to one side and half of it to the other. This is shown in the video below.

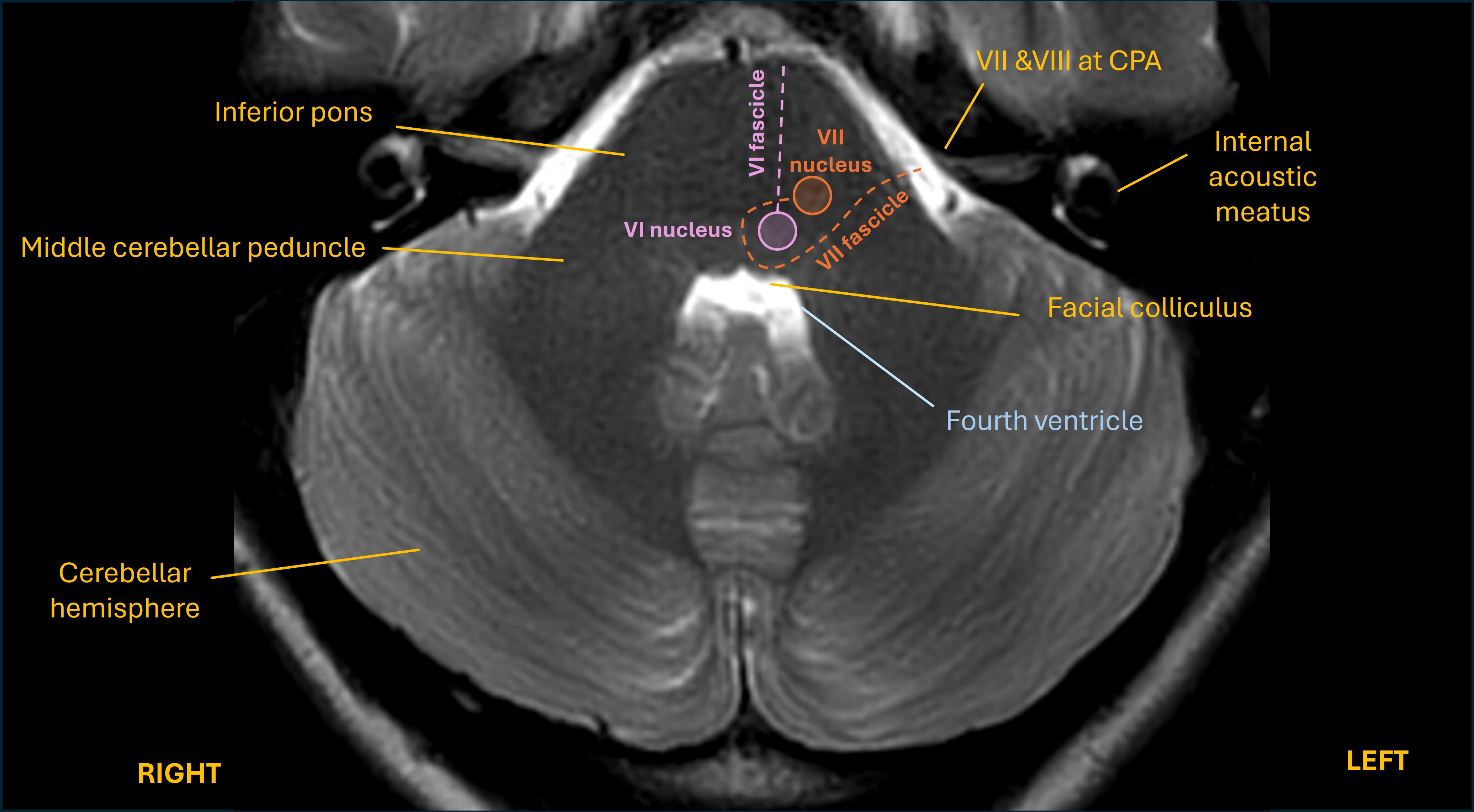

If other structures are then affected we may see additional combinations. One is when the facial nerve fibres are affected - they travel backwards and loop around the VI nucleus at the facial colliculus (which looks like a mound in the floor of the 4th ventricle).

A simpler combination is a right INO and VI palsy. Here the eye cannot adduct (except in convergence), or abduct. The left eye can move left and right, but it may have nystagmus during left gaze accompanying the right INO.

None of these features are present - so perhaps the lesion is a little higher than the inferior pons at the origin of this pathway?

SummaryWe know there's a problem in the right dorsal brainstem somewhere between pons and midbrain, as the right MLF is involved - this is supported further by skew deviation and nystagmus with central characteristics. Spared convergence suggests this is lower than the midbrain. The right PPRF isn't involved nor VI or VII. The best bet is a right dorsal pons lesion, a little higher up than the inferior pons.

What is the lesion?